U.S. Equities

Long-Term Investing

One of Claudia Huntington’s most successful investment decisions hinged on a single question. She was meeting with Lotus Development Corp., a pioneer of spreadsheet software, while the company was struggling through a challenging product cycle. The beleaguered CEO was facing heavy criticism and less than thrilled about meeting with her.

“My initial meeting was hard to get, but I was finally granted 15 minutes,” Huntington recalls. “When I entered the room I could see he was tense, bracing for the inevitable questions about the coming quarter.”

But that wasn’t her question. “I told him, ‘Let’s not talk about the next few quarters. Can you talk about your vision for where you plan to take this company over the next five years?’” The executive’s body language immediately relaxed, and the conversation ended up running two hours. “He opened up about the risks and opportunities the company faced, his long-term strategy and how he planned to execute on that strategy,” says Huntington, who liked what she heard and decided to invest.

That proved to be a good decision because the company turned around and the stock outpaced Wall Street expectations.

Of course not all her investments have worked out as well as Lotus, but Huntington believes her focus on long-term results, a trait she shares with her Capital Group colleagues, offers a clear advantage when evaluating companies and their leaders. “Quarterly results are important too but taking a longer view can lead to rich dialogue with company leaders,” she says. “Our best investment decisions are made when we are on the same wavelength as the CEO. We gain a deeper understanding of their talents and the likelihood that they can successfully navigate risks and execute their strategy.”

Huntington, who began her investing career in 1973 — a period of rapidly rising inflation and volatile markets — has decided to retire in 2020. The portfolio manager and former president of AMCAP® Fund recently sat down to share insights and lessons learned over nearly half a century as a professional investor.

What are the most important lessons you’ve learned?

I’ve learned that this business is more art than science. Early in my career I thought it was primarily about math and perfecting my model. Sure, you need math, but the more you invest, the more you realize it’s about making judgments — about people and about the future. There are no facts about the future, so you have to try to look around corners.

Perhaps the most important lesson I’ve learned is that a company’s management is essential to its ultimate success or failure. If you have a great company run by a poor CEO, the odds of that company turning into a good investment are low. On the other hand, if you have a mediocre company in a mediocre industry with a superb CEO, then it is much more likely that company will turn out to be a good investment. So, being able to calibrate CEOs and management teams is an important skill to develop.

Can you share some examples of CEOs you’ve encountered who were difference makers?

A recent example is Satya Nadella, Microsoft’s chief executive. He was not an obvious choice to run the company when he succeeded Steve Ballmer in 2014, but he has excelled for a number of reasons. One thing Satya does at the end of every meeting, regardless of whom he is meeting with, is ask, “What do you think?” The fact that he wants to encourage participation, to hear other voices, is such a demonstrable, cultural advantage.

Capital Ideas™ webinars

Insights for long-term success

CE credit available

One of the most effective CEOs I’ve ever encountered was Mark Donegan of Precision Castparts, a maker of specialty metals for the aerospace and defense industries. Donegan is a detail-oriented leader with a laser focus on productivity and a great allocator of capital. But what is most special about Donegan is the culture he has fostered at his company. He created a real sense among his employees of working together to do the right thing.

I often ask executives to describe the culture of their company. Some have great answers; others look at you like you came from the moon. The best companies are often the ones with a very strong culture.

Identifying a strong CEO is no guarantee of long-term investment success. Years ago, I invested in a company called Silicon Graphics largely because I believed the CEO was first-rate, and I had faith in his strategy for the company — a maker of specialized computer systems for graphic applications. We identified the opportunity early, and the company experienced strong growth. The investment was a good one — until it wasn’t.

The CEO eventually got interested in politics and essentially assigned running the company to a subordinate who made a series of bad decisions. I had established such trust and faith in the CEO that I didn't look more closely when changes were made. That was an important lesson for me.

How has culture shaped you as a portfolio manager?

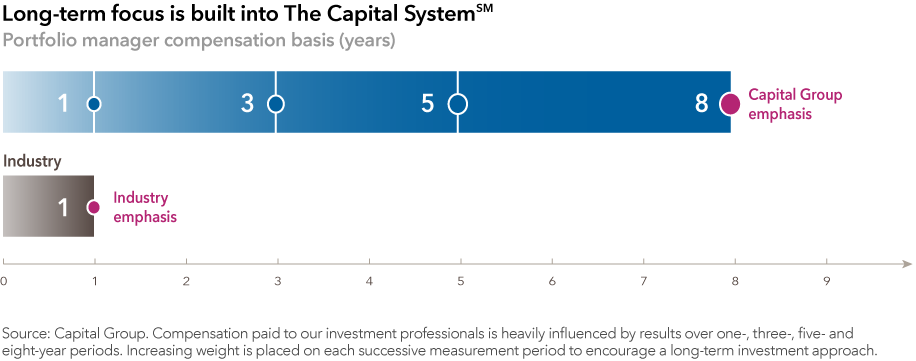

At Capital, we are encouraged to focus on long-term results. In fact, under The Capital System℠, compensation paid to our investment professionals is heavily influenced by results over one-, three-, five- and eight-year periods. Increasing weight is placed on each successive measurement period to encourage a long-term investment approach. Our culture is also designed to encourage what I call the lonely idea. By definition, good investments are not something everyone knows about. It takes a great deal of courage to identify an opportunity early on that has the potential to be a great investment.

One example of a lonely idea is Precision Castparts. On paper this company was not that interesting. It was in the industrials space, with a concentrated number of clients and limited supply sources, so there were risks. When I traveled to Portland to meet with CEO Mark Donegan, I found the headquarters on the third floor of a small unmarked industrial building next to a gravel parking lot down a dirt road. Clearly this was a cost-conscious company. I found it to be to be well-managed and operationally focused.

When I presented this unlikely investment idea to our investment group, I was challenged by my colleagues. They were polite and respectful, but skeptical. “Why would you want to invest in a specialty metals company in this stage of the cycle?” But the beauty of The Capital System, is that I could act on my conviction to invest, and by doing so I convinced some colleagues to invest with me. Our system allows that bright spark of the lonely idea to shine through — rather than being dimmed by consensus.

You began your career in a tumultuous time for markets and have seen your share of downturns. What advice do you give younger colleagues?

I started my investing career near the beginning of one of the worst bear markets since World War II. My first job was at another asset manager that had three rounds of layoffs in my first six months. Capital ended up acquiring the firm’s assets, which is how I came here. This early experience taught me that this is a very volatile business. I also quickly recognized a stark difference between the way Capital and my former employer managed uncertainty. Capital has learned to manage through volatile periods and views down markets as opportunities.

We try to reassure associates during periods of uncertainty and encourage them to focus on long-term opportunities that may arise. With the COVID-19 pandemic leading to a recession and bouts of volatility earlier this year, I shared with younger colleagues a list of 10 tips for weathering market downturns to provide some perspective from my own experiences. Among them are “don’t dwell on what the market did yesterday,” “pay attention to balance sheets,” and “keep talking to companies.” The easiest thing to do in a downturn is to just freeze, so many of my suggestions try to help colleagues manage emotions and take action.

For a primarily U.S.-focused investor, you have spent much of your time traveling abroad. Why is that important?

First and foremost, traveling gives me fresh perspective on the companies that I follow. So many companies today, whether they are in or outside the U.S., have global operations and customer bases. I can travel to India, for example, and visit a pharmaceutical business. That's going to give me perspective on all pharmaceuticals, wherever they are.

I travel to get some notion of the competitive environment, but also a sense of where challenges could come from or new opportunities. To truly understand a company — or a market or an industry, for that matter — you really have to go see it with your own eyes. You can’t do this job from a Bloomberg terminal.

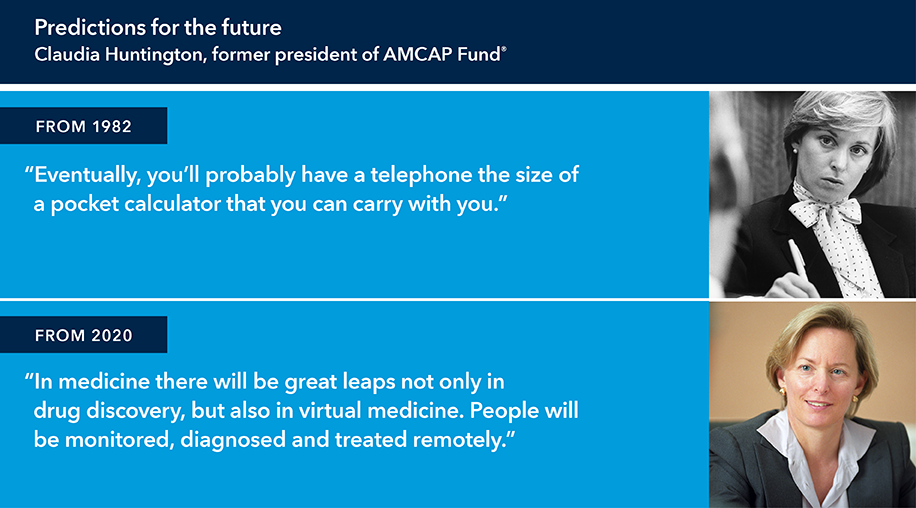

As an investment analyst in 1982, you predicted the coming of the mobile phone. How do you think the world will be different in 10 years?

I have witnessed remarkable change in my career, not only in terms of investing opportunities but also global opportunities.

When I started, there were no cell phones, no internet, not even desktop computers. I am certain there will be comparably huge leaps in the coming years. Many will be in technology, but there will be leaps in other areas. With respect to energy, I expect there will be some fabulous storage technology and better battery technology. That’s going to have a tremendous impact on the kind of transportation people use. There will be major changes in agriculture, in the way farms operate.

I think one of the most exciting areas is medicine, where I believe there will be great leaps not only in drug discovery, but also in virtual medicine. People will be monitored, diagnosed and treated remotely.

What drew you to a career in investing?

I would describe myself as someone who has always been interested in learning about the way things work. That’s what drew me to study economics in college and then to a career in investing.

What’s more, Capital has a culture that encourages lifelong learning, which really has been a perfect fit for me. In fact, as we speak I am working on a project with several Capital analysts to quantify the role that management plays in a company’s stock returns. I can’t wait to see the results of this study, and I’ll be working on it until my last day in the office!

Investing outside the United States involves risks, such as currency fluctuations, periods of illiquidity and price volatility, as more fully described in the prospectus. These risks may be heightened in connection with investments in developing countries. Small-company stocks entail additional risks, and they can fluctuate in price more than larger company stocks.

Our latest insights

-

-

Technology & Innovation

-

Long-Term Investing

-

Long-Term Investing

-

U.S. Equities

RELATED INSIGHTS

-

Markets & Economy

-

Artificial Intelligence

-

U.S. Equities

Never miss an insight

The Capital Ideas newsletter delivers weekly insights straight to your inbox.

Claudia Huntington

Claudia Huntington