In a year when soaring inflation, the war in Ukraine and a bear market have commanded headlines, the U.S. midterm elections risked becoming an afterthought. But now the election is coming back into focus. And with good reason. Capital Group political economist Matt Miller believes 2022 could be one of the more consequential midterm elections in U.S. history.

“Make no mistake, every move in Washington this year has been carefully calculated with the midterms in mind,” Miller says.

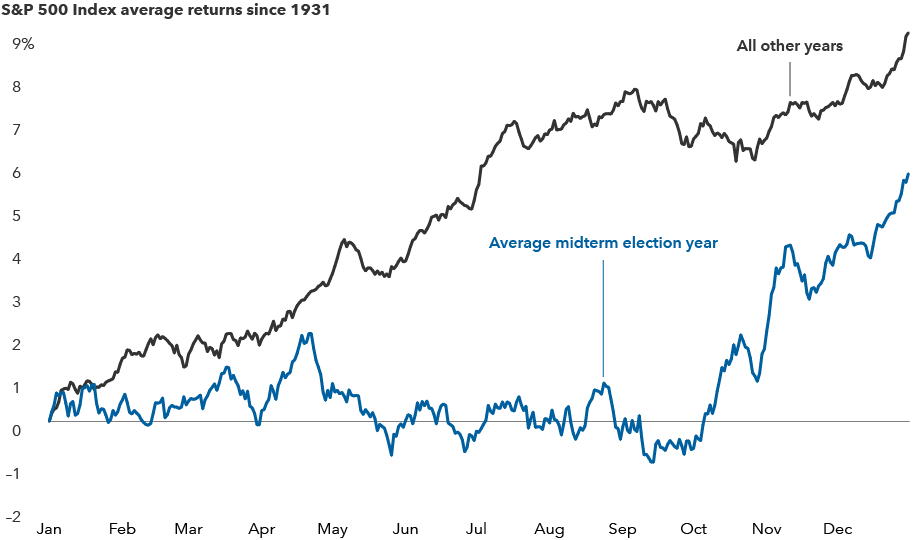

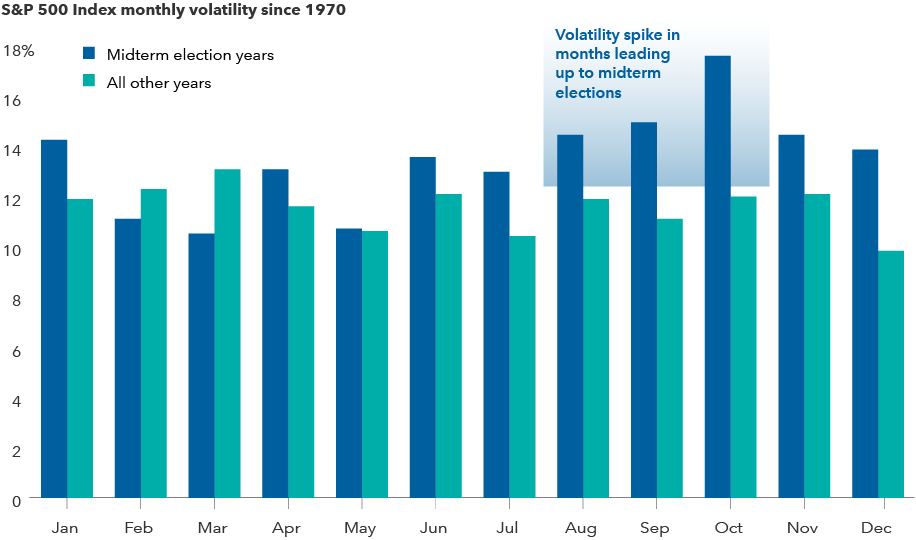

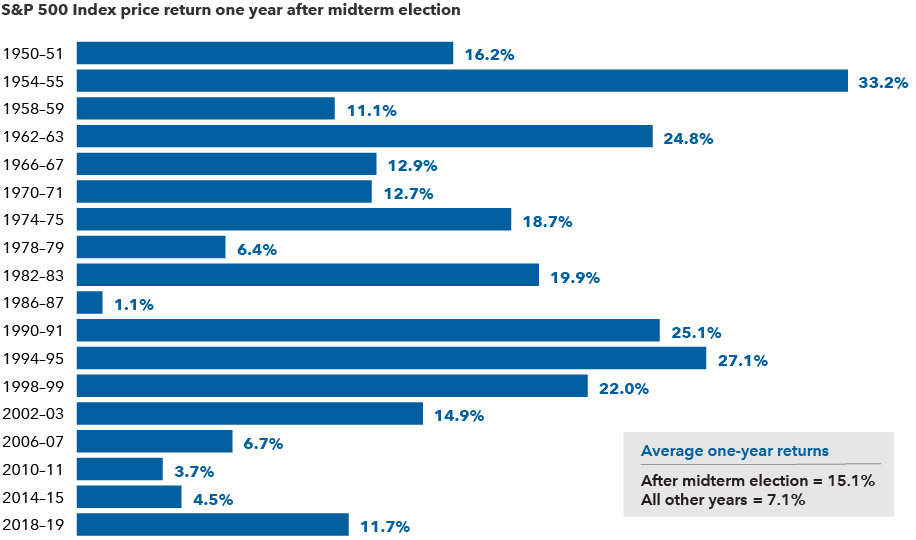

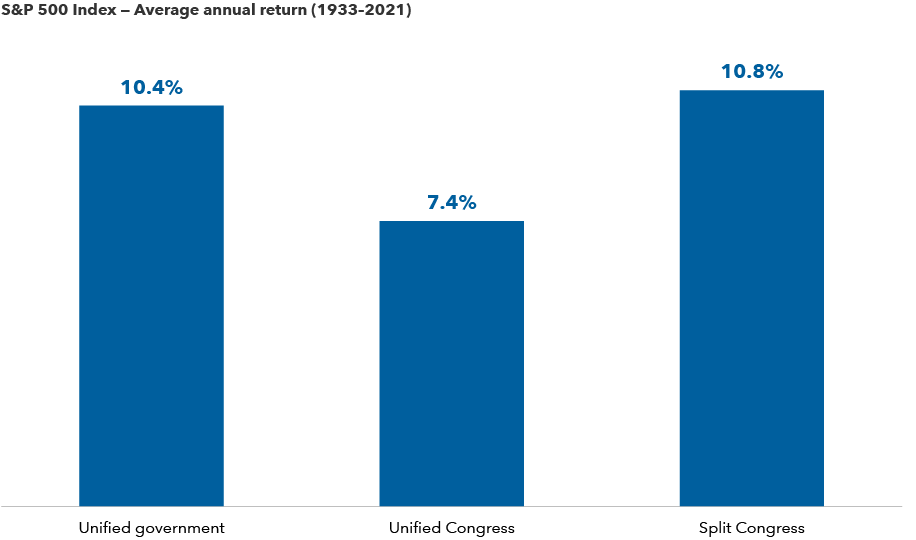

But while control of Congress may be at stake, do midterm elections have any effect on equity markets?

To find out, we examined more than 90 years of data and found that the answer is yes, markets have behaved differently during midterm election years. Here are five things you need to know about investing in this political cycle.