The U.S. Treasury market has come under pressure after President Donald Trump’s sweeping tariff announcements triggered a widespread sell-off in bonds. As policy decisions with deep financial implications are rapidly made and reversed, it is understandable that holders of U.S. assets might feel a sense of unease.

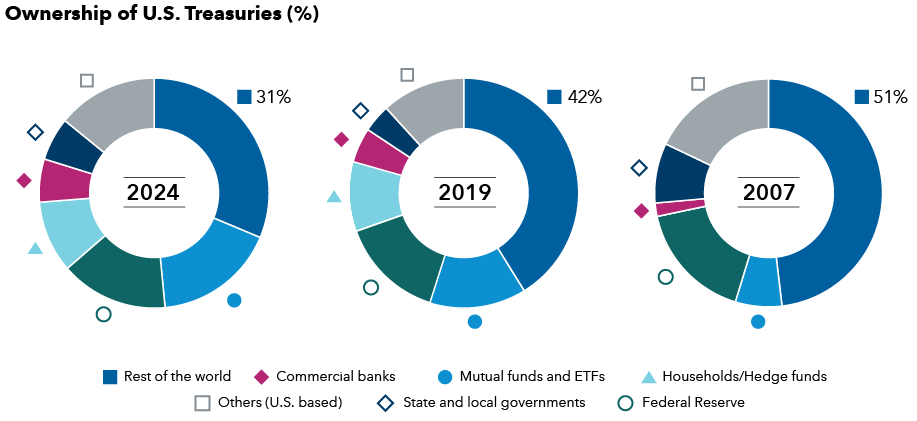

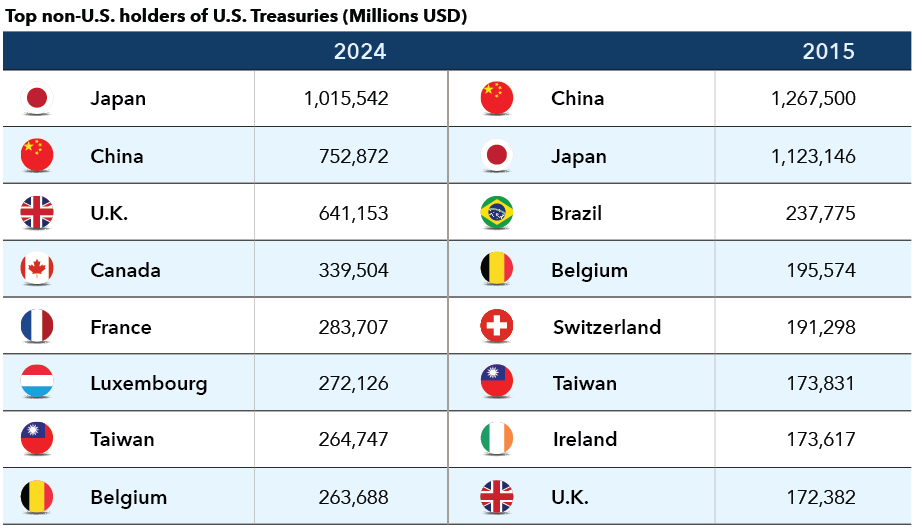

Two factors are at play in the Treasuries market: the large volume of investments by hedge funds and other investors in highly leveraged trades, as well as foreign investors potentially stepping away to diversify assets from the U.S. Some investors have grown concerned that this turmoil could be on the verge of creating a liquidity event, where Treasuries cannot be easily bought or sold without causing significant price changes. Should the market reach a breaking point like during the COVID-19 pandemic, we think the Fed will be quick to react, but probably not with rate cuts, given the uncertainty surrounding future inflation.