In a televised address from the Rose Garden with a U.S. flag as the backdrop, President Trump plunged the world into uncharted territory by forcefully rejecting unfettered free trade as part of a broader realignment of U.S. interests.

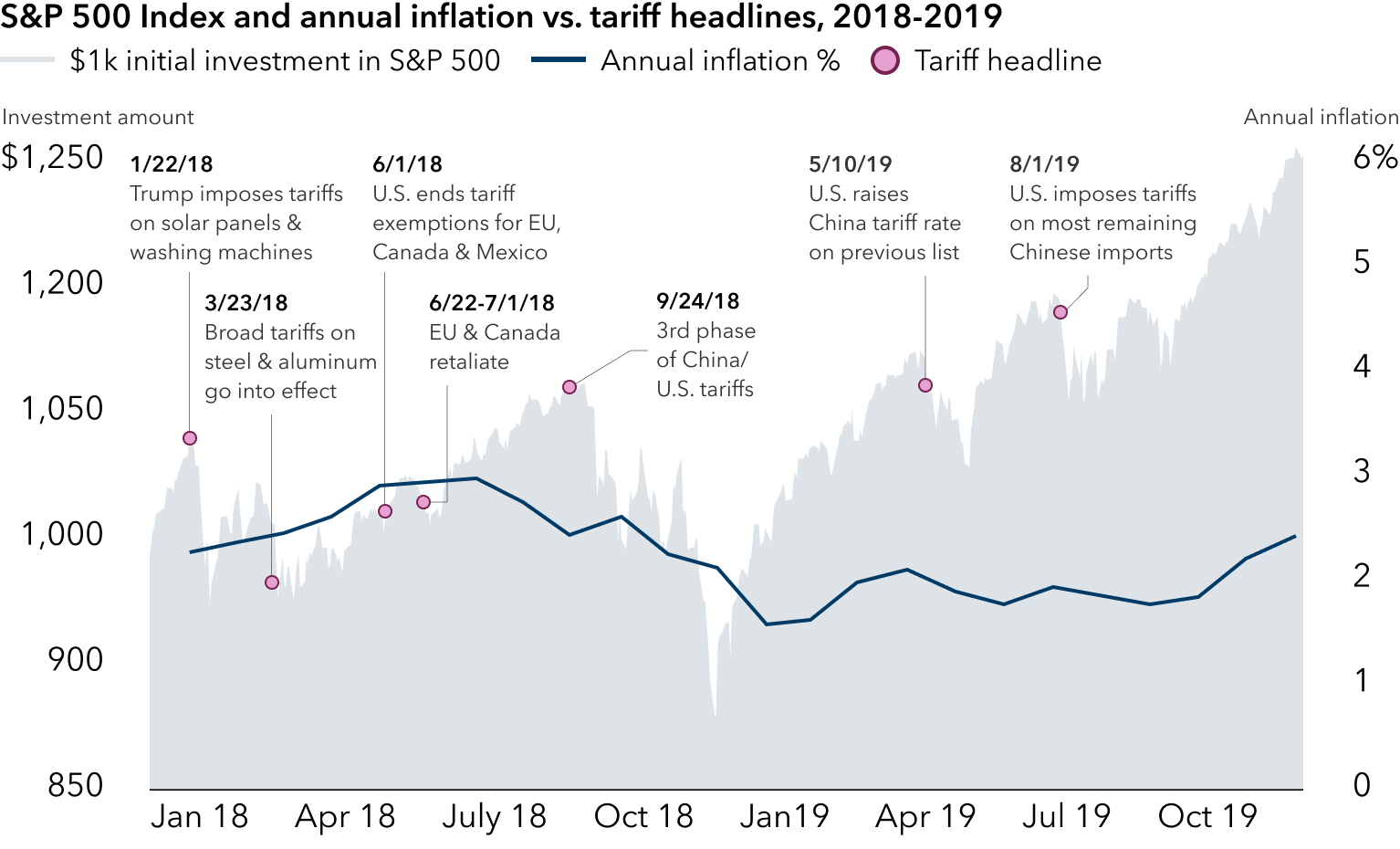

Trump unveiled a 10% tariff that will apply to most countries and imposed harsher rates on a long list of trading partners including China, the European Union and Japan. The expansive measures — which follow tariffs on autos, aluminum and steel announced in March — roiled markets and raised the prospect of a global trade war. The S&P 500 Index plummeted 4.84% on April 3, 2025, extending year-to-date losses.

President Trump’s effort to revive U.S. manufacturing and raise government revenue via tariffs will test longstanding trade relations. Tariff uncertainty has caused businesses to pause capital spending and hiring plans. Consumer spending, which represents about two-thirds of the U.S. economy, also appears to be slowing.

Nevertheless, investors shouldn’t extrapolate too much from the uncertainty. For one, we are in the early days of Trump 2.0, and the ultimate outcome may differ from the initial headlines. There will likely be more tariff turbulence throughout Trump’s presidency. To help make sense of it all, we answer common questions about tariffs and their potential implications for the economy, markets and investors.