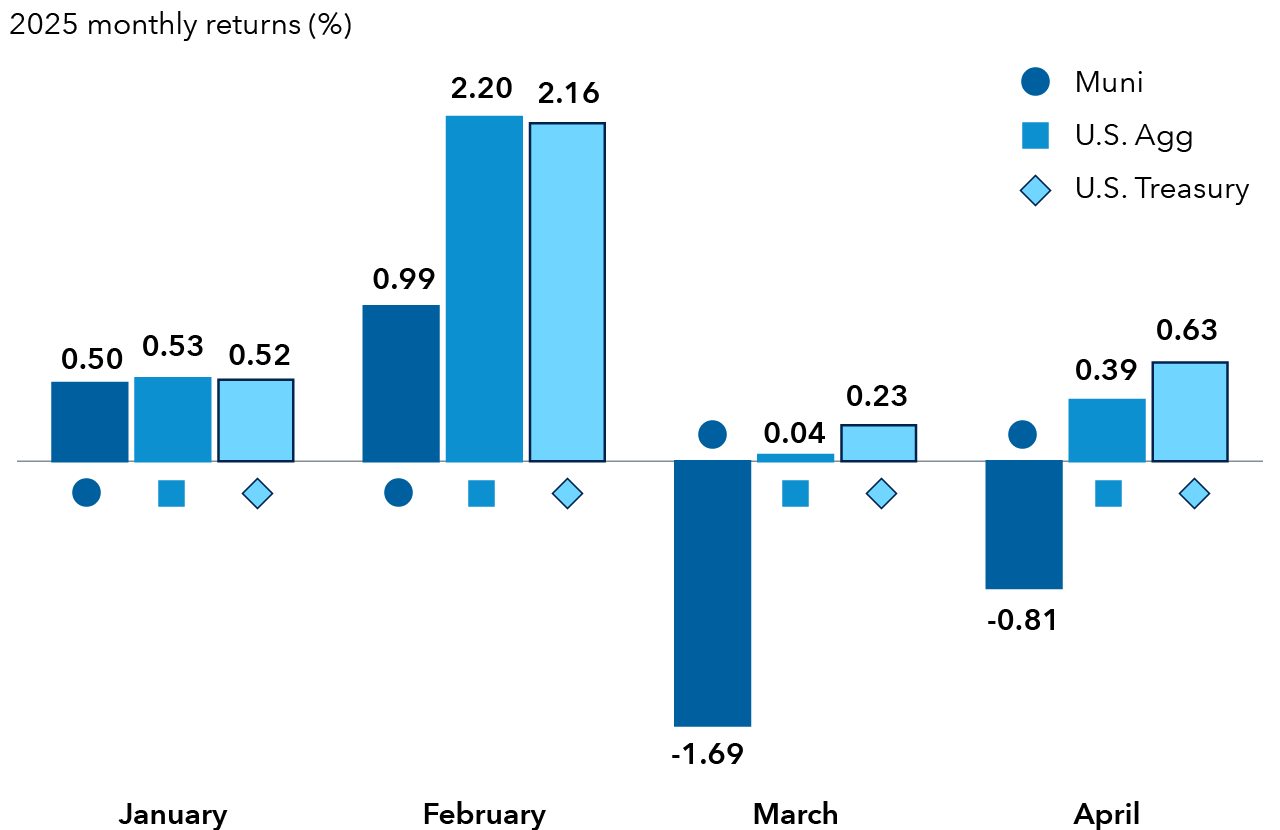

We see three major factors to consider when analyzing the muni volatility experienced this year:

- Counterparties (a partner in a financial transaction) have been stepping away due to overall financial market uncertainty. Financial institutions usually play an important role in the muni market turmoil by acting as a liquidity provider and market buffer. Increased risk has led them to step aside in recent weeks.

- Exchange-traded fund (ETF) redemptions. We’ve seen an uptick of ETF redemptions, which tend to happen in larger swaths. The muni market acts as a flow market, so outflow cycles meaningfully affect muni market results. We see this as a temporary move and not one likely to escalate and lead to a broader sell-off.

- Higher grade munis are more liquid and first out the door. This supply hitting the market has led to a more adverse price impact to high-grade munis in the short term.

Longer term concern is that this market movement causes retail investors to move to cash and we see an investor-led outflow cycle. These tend to be longer in nature and could lead to further weakening. The muni market is 66% owned by retail investors (45% directly and 21% in muni bond funds), so changes in their behavior could have meaningful impact on the market.

Uncertainty remains high given a lack of clarity on policy and individual headlines often heightening volatility. Recession risks appear to be rising meaningfully even as inflationary pressures may also be building, creating potential for a stagflationary shock (a period of rising unemployment, low economic growth and rising prices).

Moreover, we expect federal spending cuts, particularly in the education and healthcare sectors, to have a more notable and immediate impact on municipal credits compared to tariffs.

Our portfolio managers are maintaining up-in-quality postures and neutral-to-overweight duration stances. As valuations come under pressure and volatility persists, we believe our portfolios are well-positioned to take advantage of dislocations and attractive opportunities.

Will the tax exemption expire?

Nearly 75% of the infrastructure in the U.S. is financed by municipal (muni) bonds. Tax-exemption for muni bonds dates back to 1913. As a pillar of the U.S. financial system, muni bonds allow state and local governments to fund, with low-cost borrowing, essential services, including roads, sewer systems, public education, parks, hospitals and more. Funding is plentiful in part because investors who purchase the debt of these municipalities are exempt from paying federal income tax on the income they provide. Munis are also a relative safe haven, with a lower default rate than global corporate bonds. As a result, muni bonds can be an attractive asset class for income investors looking for relatively low-risk tax-efficient investment strategies.

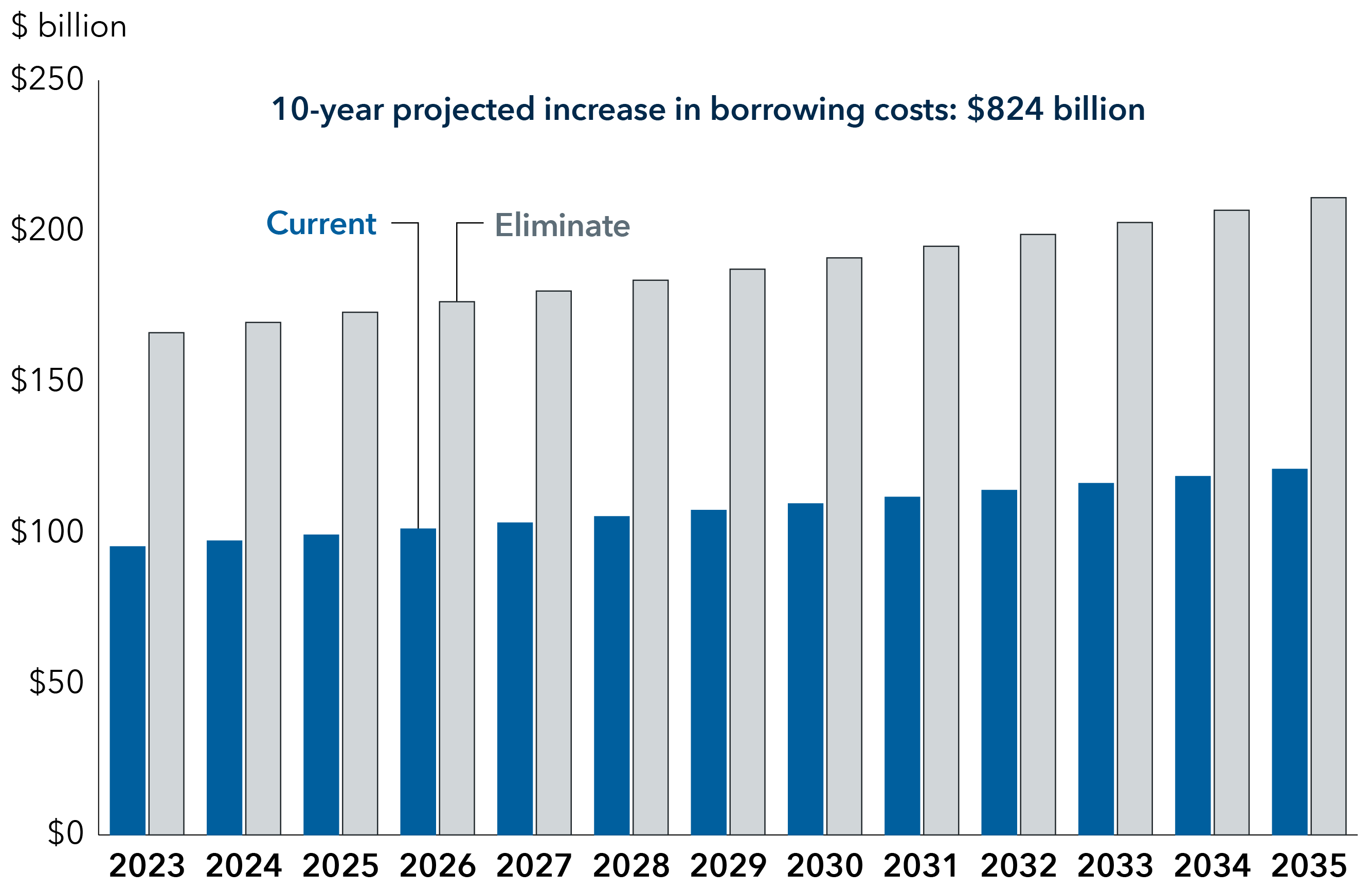

Which brings us to the first worry plaguing some investors: the expiration of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). With a budget hole to fill, there have been some whispers of removing the tax-exemption status of munis. In January, a U.S. House Ways and Means Committee proposal included the line, “eliminate exclusion of interest on state and local bonds.” These nine words triggered some unease, and served as part of the reason why the muni market cheapened relative to the taxable bond market in the first quarter of this year. The proposal instilled a seed of doubt in investors, and caused issuers to bring deals earlier than they might have otherwise, resulting in an increase in supply of muni bonds. A total elimination of the tax-exemption could lead to higher borrowing costs, strained budgets, changes to essential services and other material impacts. In new developments, the full, updated draft of the U.S. House tax committee's reconciliation bill released on May 12 did not seek to remove the broad muni tax exemption, but did contain a few provisions that could have a negative impact on some sectors, if adopted.

Overall, we view the removal of the tax exemption as a very unlikely scenario for a few reasons. First, it would be very hard — or nearly impossible — to implement retroactively on existing municipal issues. Thus, if implemented, it would likely be on a “go-forward” basis only for new issues. The way budget math works, this would amount in a relatively tiny deficit reduction.

Second, while the U.S. House budget document estimates that eliminating the exemption would add $250 billion over 10 years, the Public Finance Network (PFN) says it would cost cities and states $824 billion in higher borrowing costs. As such, this would become a bipartisan issue. To supplement those costs, state and local governments would be forced to raise taxes. According to the PFN, this could result in a $6,555 tax and rate increase for individual households over the next 10 years.